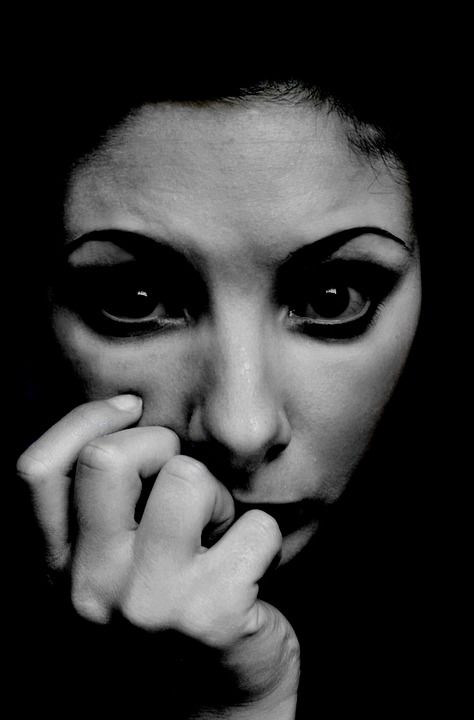

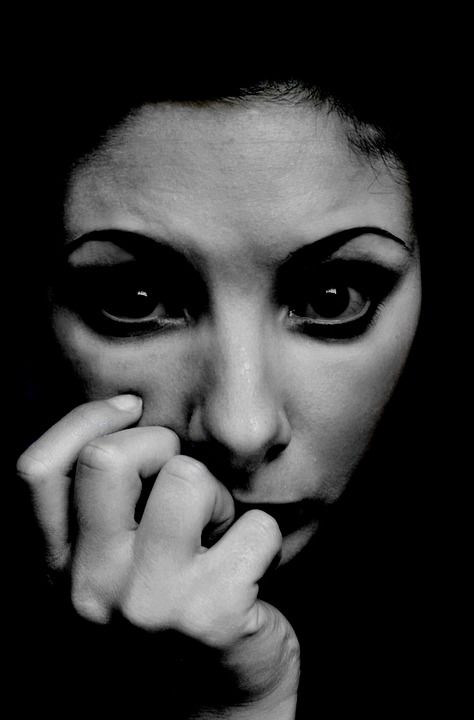

Think of a time where you just couldn’t stop something from popping up in your head. Whether it was a song lyric to that Katy Perry song you didn’t even like, or a cringe-worthy memory of your failed punch-line during that date you went on six years ago. As it happens, it’s often the negative things that like to remain on mental repeat without our conscious permission.

Intrusive and unsolicited memories are something we all experience every once in a while. For some, they’re mostly innocuous - annoying little quirks of the mind. But for others, like those with anxiety and OCD, the uncontrollable thoughts can wreak havoc on basic mental functioning.

Unwelcome thoughts, especially those related to one's sense of self, can hinder optimal functioning.

The question is, who has control over their (negative) thoughts? And why? Researchers are now coming to understand that we have designated neural defense mechanisms preventing intrusive thoughts from completely hijacking our brains. In particular, it’s a neurological control system in the prefrontal cortex, a brain area involved in executive control and, in this case, in the inhibition of intrusive thoughts.

The system, however, isn’t perfect all the time. And it’s this dysregulation that could perhaps explain the basis of many different psychiatric disorders including PTSC, GAD, OCD, and schizophrenia.

Now, researchers are learning that it could be related to another candidate brain region beyond the prefrontal cortex – the hippocampus. Hippocampal activation, we’re coming to understand, seems to be involved in pathological cases of intrusive thoughts.

The Hippocampus and thought intrusion: What do we know?

The neurotransmitter, GABA, which is known for its inhibitory properties, has been linked to dysregulated hippocampal activation and pathological instances of intrusive thoughts. But the actual mechanisms underlying hippocampal-related GABA activity and the control over intrusive thoughts remains a mystery.

How exactly does GABA in the hippocampus contribute to preventing unwanted thoughts? Dr. Taylor W. Schmitz and colleagues, a group of neuroscientists out of Cambridge University, hypothesized a link between GABA’s activity in the hippocampus and the brain’s pathway to the prefrontal cortex. It’s this system together, the researchers predicted, that helps keep our intrusive thoughts in check.

The researchers used a task called the ‘Think/No-Think’ procedure where participants learned to associate pairs of words that were unconnected in their meaning. For example, apple/motorcycle or telephone/cucumber. Participants were asked to recall the associated word when they were shown a green cue, or to suppress it when they were shown a red cue. If they were shown ‘apple’ in green, they were asked to think about the associated word ‘motorcycle’ and vice versa.

The researchers observed participants’ brain activity using a combination of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and magnetic resonance spectroscopy. The fMRI allowed them to observe activity level in the key brain regions of interest while the spectroscopy helped them measure the underlying brain chemistry.

Dr. Schmitz and colleagues found that participants with less hippocampal GABA had impaired function in the suppression of hippocampal activation (i.e., greater levels of activation were found in the hippocampus during the task). The impaired hippocampal activity, in turn, led to compromised prefrontal control, which then reduced one’s ability to suppress thoughts during the ‘Think/No Think’ task.

What this means and future directions

The research successfully uncovers a link between proposed control mechanisms in the prefrontal cortex and GABA activity in the hippocampus. Traditional theorizing saw the prefrontal cortex as the primary gateway for the control of unwanted, negative thoughts. But here we’re seeing that hippocampal activation, and reduced GABA in particular, forms the basis of this thought control pathway in the brain.

The findings provide insight into why we tend to observe increased hippocampal activity in psychiatric disorders like schizophrenia. The unwanted thoughts and images resulting from hyperactive hippocampi could explain, for example, why patients of schizophrenia often suffer from hallucinations, among many other anxiety-related symptoms.

Future directions could consider the hippocampal GABA activity of psychiatric patients and might pave the way for treatment of pathological thought intrusion. Alterations in pharmacological interventions could be of interest for future researchers and practitioners.

No comments:

Post a Comment